Choose Your Conspiracy Carefully

The people in the U.S. are navigating through the choppy waters. I think of this as the gulf of conspiracy. Less than a month ago, my visit to the dentist demonstrated this. Prior to entry, much care was taken — “Call before entering when you arrive. Let us know if you have a fever or other symptoms? You must wear a mask.” Good. A place of care. Once inside, however I found another contagion. A pandemic of conspiracy, spread by a friendly staff member. As we talked, she opined that “COVID-19 deaths are exaggerated so that doctors and hospitals can make more money.” Okay, I thought — that’s a new one — a pretty sad and inaccurate one — given the risks being taken by medical staff and the financial distress many healthcare systems face in this dramatically changed economic reality.

However, that wasn’t the first touch with conspiracy that morning. A phone call earlier from a friend began, “Don’t you think Donald Trump is pretending to have the corona virus and doing this for political purposes?” “No,” I responded, “How would this be helpful?”

Our nation seems to be swimming in a sea of conspiracies. Today there is the claim of “widespread voter fraud” by President Trump and his most loyal supporters. There is no evidence. Election officials, including Republicans, deny this in states where such “fraud” is claimed to have occurred. This conspiracy joins ranks of others in 2020 like the anti-vaxxers who oppose all vaccines, the belief that Vladimir Putin has compromising information on Donald Trump and the idea that COVID-19 was deliberately produced in a Chinese lab.

I hear multiple conspiracies each day. Some are minor and some perhaps carry a small grain of truth. Ever hear of Area 51 in Nevada or the various theories behind the assassination of President Kennedy, or that Neil Armstrong didn’t really walk on the moon? Other conspiracies offer more existential and long-term danger: like those labeling all media as “Fake News” so as to undermine all news sources, or the claim that climate change is a hoax even as our natural environment may be irreparably damaged, or the astonishing QAnon assertions that Tom Hanks joins the Democrats in cannibalism and child sex-trafficking.

Presidential elections are fertile ground for new conspiracies. Those who start political conspiracies behaved like rabbits this year, breeding and releasing multiple distortions and threats into our civic life. We need take great care in choosing which conspiracies shape our understandings. You say – “Hey, wait a minute there, fella, I don’t fall for conspiracies!” Sorry, I have some sad news to report. From many research quarters (universities and sophisticated research centers) comes the knowledge that everyone is prone to accepting ideas that bolster preconceived notions. Confirmation bias is alive and well. It is the notion that we choose the information that reinforces our beliefs and values.

Am I saying that we are stuck in our conspiracies? Well NO, and, sadly, potentially yes. Conspiracies do not an entire worldview make; however, our worldviews do make us more susceptible. Here is where the value of the intervening correctives come into play. Reason, research and faith-informed reflection are a critical trio for me. Other correctives are enshrined in our nation’s constitution and bill of rights. Still others are operational — things like continuing education, practicing critical thinking, reading widely, legal precedence and community engagement each can assist in holding our hubris and distortions in check.

For years I have felt something important is lost as religious congregations have become more and more monolithic in make-up theologically and culturally. Genuine and durable democracy and respect across ideological divisions was often bolstered in friendly disagreements across the table at the pitch-in dinner or visits after worship in the parking lot.

There is a sign along the Alaskan Highway that reads “Choose Your Rut Carefully. You’ll Be In It For The Next Sixty Miles.” I hate to admit it, but I am old enough to remember such signs as my family traveled across Missouri and Oklahoma back in the early 1950s. Of course, then it was only a few miles in the same rut. The conspiracies to which we may fall prey can turn into ruts that mislead and distract for years.

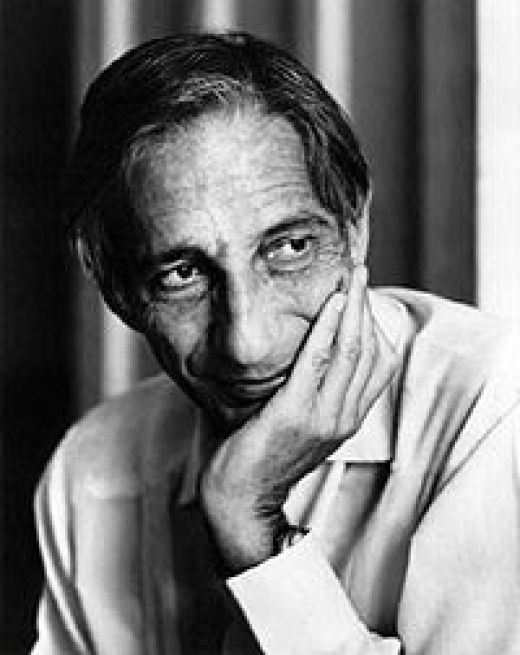

As I think of conspiracies and the rut I choose, I am am reminded of Ivan Illich, priest and social critic. Illich speaks of “conspiratio” and “comestio” as essential to faith and the civic life [See David Cayley’s conversations with Ilich in “The Rivers North of the Future,” Anansi Press, 2005].

Illich asserts that conspiratio is not a bunch of rebels trying to undermine or overthrow a political order. It is not the sowing of misinformation or deceit. It is more radical than this! It is about living by a new narrative. It is a changing of the “I” into a new “We.” It is the Gospel narrative set out in the parables of Jesus. Stories of Good Samaritan, the Importuning Widow, the Ten Bridesmaids, and on and on and on the parables go. There are stories of those celebrating the finding of that which was lost, and of the best wine served late and with abundance. There is a conversion of what is presumed to be a suspicious and limited existence toward a community of abundance and conviviality. It is the narrative of God’s grace and the joys of faith over against the dominant grim order. It is about that which was lost, being found. Conspiratio is “breathing together,” represented in the “kiss of peace” offered as believers come to celebrate the Eucharist. Comestio is the sharing of a common meal where all are welcome at the table.

I have not done justice to Illich here; still let me affirm that he points to the conspiracy into which I choose to live.

This morning as I walked my normal route contemplating how to end this reflection an incident occurred that surely comes as a sign for me of the conspiracy I choose. My walk took me through a neighborhood park named in memory of Dr. Ernest Butler, an African American pastor in Bloomington and friend of mine for many years.

Along the trail, between the playground and tennis courts, a man in his mid-forties approached. He motioned and asked if I could help. I nodded yes, not certain what he wanted. He said, “Have you seen a boy on the trail, sandy haired?” Raising his arm he gave indication of the young man’s height. “No,” I replied, “If I see him what do you want me to tell him?” The man choked back his words, wetness welling in his eyes, “Tell him, his father loves him. He should come home.”

I walked on. A half an hour or so later I saw the father and boy sitting together on a bridge, talking. May I live to see such conspiracies often.